LONDON > PARIS

LONDON > BRUSSELS

2007 | United Kingdom, France, Belgium

Journey

More Info

- Length in km: London-Paris: 342 km

> Channel Tunnel: 22 km and 360 trains/day

> London-Brussels: 321 km - Name of the train: Eurostar

The birthplace of railway pioneers since 1825, Great Britain is today connected to the European continent thanks to rail. The Channel Tunnel, a major challenge of the 20th century, has not only overhauled regional development on both sides of the Channel; it also serves as a vital link in the European rail network. Marking a major turning point for rail in Great Britain, the tunnel led to the construction of Britain’s fi rst high-speed railway line, opened between 2003 and 2007, thus reducing journey times to France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. This new line also marks the fi rst step towards a future national high-speed network, part of the giant “High Speed 2” project that will link the capital with major cities in the northwest of England.

Summary

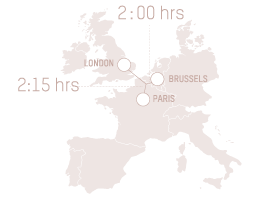

Leaving London

Eurostar sets off for the continent from one of the most dynamic cities in Europe. With this train, London, the ultimate cosmopolitan city with all its contrasts, traditions, and eccentricities, is now only two hours and fifteen minutes from Paris, and two hours from Brussels. Just a stone’s throw from the Greek temple-like dome of the British Museum, and adjacent to the esteemed British Library, stands the rail station of St Pancras International. This successor to London Waterloo, the original departure station for Eurostar, has earned a new lease on life with the construction of the high-speed line. Its dynamic surrounding neighbourhood, embellished with generous squares, pedestrian streets, and leafy parks, is now highly sought after, especially by London executives.

A proud Victorian (1837–1901) edifice, Saint Pancras International is clad entirely in red brick, resembling a neo-Gothic palace. Saved from demolition in 1960, the station underwent renovation at the beginning of the 2000s and re-opened in 2007. Under the spectacular arched roof of the Barlow train shed, the length and number of platforms have been doubled to accommodate the 400-metre-long Eurostar trainsets. The station’s two levels boast a shopping centre, restaurants and cafes that attract passengers from all over the world. Together with its neighbour, Kings Cross Station, St Pancras International forms the heart of a transport hub for the capital.

Channel Tunnel – an epic tale!

For 200 years it was the stuff of dreams for engineers on both sides of the

Channel. Riding, walking, or galloping under the sea, everything seemed

possible... in theory. As a result, dozens of studies for fixed links between

France and England were put forward but led nowhere.

In 1802, the French engineer Albert Mathieu had already imagined a paved

tunnel with two galleries, built one over the other, and an artificial island

in the middle for resting carriage horses. A year later, the Englishman

Henri Mottray in turn explored the possibility of an underwater tunnel

composed of metal sections. From 1830, the idea of a railway tunnel

gained popularity. When Thomé de Gamond presented his plans for a

bored tunnel at the 1867 Universal Exhibition in Paris, both Napoleon III

and Queen Victoria reacted with great enthusiasm. Thirteen years later

saw the first attempts to dig from both sides of the Channel. Excavation

work was soon halted by Great Britain, reluctant to lose its island status,

and by France for reasons of military defence.

In 1955, the “bridge or tunnel?” debated began anew between the two

governments. And tunnel it was. Drilling was interrupted, however, in 1975

for economic reasons. It wasn’t until eleven years later that the dream

would finally become reality. During a Franco-British council meeting, British

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and French president François Mitterrand

both brought up the subject. She spoke about her dream of driving by

car along a private bridge to France; he spoke of entering England by train.

The railway tunnel won the day. But Margaret Thatcher imposed one condition

on the project: it had to be financed entirely by private funds. The

Treaty of Canterbury, signed on 12 February 1986, endorsed the Franco-English

agreement. Eurotunnel proposed a double rail tunnel, and was awarded

the tender. On 6 May 1994, the tunnel was inaugurated. Six months later,

the first Eurostar train entered commercial service.

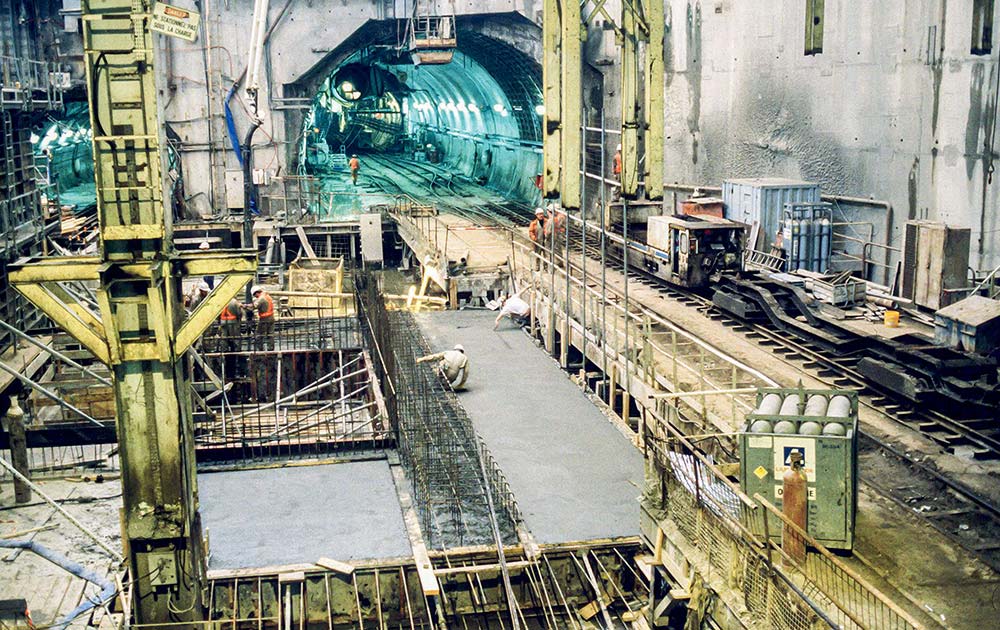

The tunnel – an industrial adventure

A technological breakthrough, with its highly sophisticated railway system, the Channel Tunnel remains one of the finest examples of engineering and human achievements, employing a workforce of almost 12,000 during the six-year-long construction period. Between Folkestone (Kent) and Coquelles (Pas-de-Calais), three parallel tunnels were bored, each 50 kilometres long, of which 38 kilometres run under the sea. The two rail tracks are connected to a service route (suitable for vehicles) for evacuating passengers in the case of an emergency. The underwater route was meticulously chosen by geologists to pass through a layer of blue chalk, known to be resilient and waterproof.

Works began in 1988 on both sides of the Channel, with giant, 200-metre-long tunnel boring machines (TBM) custom-built and assembled within the tunnel itself. At 40 metres below the surface of the sea, they crushed the chalk for months on end, at a daily advancement rate of about 16 metres. Immense, gently-curved concrete segments gradually clad the inner circumference of the tunnels to form veritable armour. The main difficulty, impossible to assess in advance with any precision, was joining up the two parts drilled from either side of the Channel; the authorised margin of error was just 2.5 metres! Mission accomplished. On 1st December 1990, media and politicians assembled to celebrate the historic breakthrough meeting between the British and French teams. Following this civil engineering exploit, by far the most complex operation was installing the railway system in the humid atmosphere of the underwater tunnel, which complicated the electrical insulation of the track circuits. Furthermore, safety requirements imposed by the French-British Intergovernmental Commission (IGC), together with new demands as the works gradually progressed, meant that engineers were constantly obliged to adapt, at considerable extra cost. Today, the tunnel is a success. Speed, comfort, safety: the tunnel links are in great demand by both countries. The major innovation introduced by Eurotunnel, the tunnel management company, was to offer shuttle services from the French and English terminals: some to carry cars and coaches; others dedicated to trucks. Eurotunnel has also become a rail freight business, handling goods wagons between Lille (France) and England.

Eurostar International

Eurostar International, a joint subsidiary of French Railways (Société nationale des chemins de fer français, SNCF), L&CR (British company London and Continental Railways), and SNCB (Belgian railway company), has become an independent railway company. SNCF retains 55% of the capital and SNCB 5%, with the remaining shares owned by a consortium composed of the Canadian pension fund Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ) and British investment fund Hermes.

High-speed in Britain

Eurostar runs along the high-speed line until the tunnel at a maximum speed of 300 km/hr. Initiated in 1996, two years after the Channel Tunnel opened, building this first line proved to be a massive challenge. A first section entered service in 2003, between Folkestone (tunnel exit) and Fawkham Junction, via Ashford station; the second section, connecting to London and St Pancras International was inaugurated in 2007. Technological expertise really came into play for the 22 km of tunnels running in part under the London suburbs as well as the viaduct over the Medway River. Both infrastructures proved to be sensitive, and costly. While the main purpose of this line is to carry passengers faster between European capital cities, Great Britain also took this opportunity to introduce to the new high-speed regional rail services operating at 220 km/hr in Kent, as well as night-time freight trains operating to and from the Channel Tunnel.

→ View of the north side of Maidstone in Kent, England.

London-Paris, the journey

A journey lasting just over two hours between London and Paris, yet a complete change of scenery! After

leaving Saint Pancras International, the Eurostar crosses the Thames and suburbs of London, partially

underground, then races into the heart of the green and pleasant landscape of Kent with its charming

cottages, castles, and enchanting gardens. The charm of the gentle English countryside. Eurostar

passes first through Stratford International station, where the Eurostar maintenance facility is located, then

the stations of Ebbsfleet International and Ashford International. Well-connected to the rest of the

national rail network, this last has rehabilitated its town centre and developed new activities.

A beeper sounds. Thirty-five minutes after leaving London, the train plunges into the Channel Tunnel.

Any fears are short-lived. One can only marvel at this feat of construction ingenuity achieved by the

engineers, the unsung heroes of this technological achievement. Just 20 minutes later, the train

reaches France.

The station at Calais-Fréthun serves coastal towns along the English Channel. A few slag heaps and

miners’ cottages, reminders of the region’s mining past, small villages with their brick buildings… the

train crosses the vast farmed plains of Picardy, under sweeping, luminous skies. Compiègne, Chantilly,

royal names, magnificent forests… and all too soon the suburbs of Paris. The Sacré Coeur basilica

greets us from the hilltop of Montmartre and the train enters Gare du Nord station.

→ Passengers at St Pancras International Station in London.

A European line

Building a vast European network was one of the main driving forces behind construction of the two high-speed lines connected by the Channel Tunnel, for both the French and British. On the French side, Eurostar trains take the northern line, linking Lille and Paris, Lille and Brussels, then Rotterdam and Amsterdam (the Netherlands). Lille-Europe is the central hub of the line, offering customs services between Paris, London, and Brussels. In April 2018, the first Eurostar train left St Pancras International for Amsterdam. In the future, plans under consideration for more international routes include London-Geneva and London-Frankfurt.

Thanks to the restructuring of the high-speed rail network in the eastern Paris region, Eurostar now serves several destinations in France: Disneyland Paris, accessible via Marne-la-Vallée-Chessy station; the city of Lyon; the Alps in winter with Eurostar ski train; Provence in summer, via Avignon and Marseille. A service between London and Bordeaux in southwestern France is being considered for 2020.

→ Eurostar e320 at Gare du Nord Station in Paris.

The star of Europe

The first Eurostar trainsets, unveiled in 1994, adopted a boxy,

narrow design in order to run on the classic English gauge

tracks running into Waterloo Station. The latest generation of

Siemens-manufactured rolling stock, however, boasts a

more rounded and spacious design, as the trains no longer

operate on the former narrow-gauge British network. The

colour scheme of yellow, blue, and grey lends an air of British

elegance. With the opening of new European routes serving

Germany and the Netherlands, rolling stock has adopted

international standards. The new trainsets have space for

more passengers: seating for 900 compared to 750 for the

previous generation, and 18 long cars instead of 16 short

cars.

For the interior design, Eurostar brought some famous names

on board. After Philippe Starck in 2003, the man behind the

iconic Ferrari and Maserati brands, Italian automotive

designer Sergio Pininfarina, redesigned the layout. With blue

and grey for 2nd Class, and hues of brown and beige for 1st

Class, the passenger cars are elegantly sober. Reclining

seats, power outlets, a mobile phone application, information

display screens in each car and a welcoming buffet further

enhance the service offering. Upon departure and arrival,

passengers are greeted by Eurostar staff in attractive uniforms

that mirror the train colours. The operator’s original

yellow, blue, and grey logo was refreshed in 2010, placing

emphasis on the ‘e’ of ‘Eurostar’ and ‘Europe’. The silver-grey

letter ends with a flourish, like a wave, over the Eurostar

brand name. In 2017, the logo was revised in blue.

Eurostar provides information on the journeys and foreign

travel destinations, as well as promotion of its on-board service.

In Paris, London, and Brussels, stylish lounges are provided

for Business Premium passengers. What a pleasure to

await one’s train seated on a comfortable velvet or leather

sofa, in a cosy atmosphere conducive to work or relaxation.

Paris Gare du Nord and Brussels-Midi

The two main destinations for Eurostar are Paris and Brussels. To reach the centre of the French capital, the train from London enters Gare du Nord, the busiest station in Europe in terms of traffic – 700,000 passengers each day. Having long played an international role, the station also serves Thalys trains arriving from Belgium and the Netherlands, TGVs on the northern France line, and a segment of the Paris suburban network. In the 1990s, the tracks were reorganised and platforms extended to 400 metres. To alleviate congestion in the station at peak hours, passenger flow, sales and information points were revised and redesigned in 2018.

This station is undergoing a vast renovation and extension programme scheduled for completion before the 2024 Olympic Games. Departures and arrivals will be separated on different levels, similarly to airports. Eurostar arrives at Brussels-Midi station on Belgium’s high-speed line. Many English passengers commute to the city’s dynamic European district, while visitors are likely to head for the Grand Place, with its opulent and utterly unique guild houses. Brussels-Midi is well connected to the Belgian transport network – trains, metro, and the tramway. Since 1992, part of the station serves as a dedicated reception area for Eurostar arriving from London as well as high-speed trains operating between Paris, Amsterdam, and Cologne. At that time, the neighbourhood surrounding the station experienced significant transformation.

Eurostar, Britain’s first choice

In terms of international relations between London, Paris and Brussels, the majority of Eurostar customers hail from Great Britain. This cross-border high-speed train has shaken the transport landscape by attracting a significant share of airline customers, as well business from ferries sailing between Calais and England. Eurostar has also revolutionised the world of business and finance between London and Paris, as 40% of passengers travel for business. Hundreds of French passengers ride Eurostar every day; many of them have moved to the City to work, study or develop start-up companies. English passengers particularly enjoy the routes established to serve Disneyland Paris, the Alps in winter, and Provence in the summer. Eurostar stimulates tourism and many travel agencies offer non-European tourist day trips to Paris, London, or Brussels on Eurostar. As is the case in the north of France, high-speed has had a major impact on population movement and regional development in the south of England. Today many Londoners live in Kent, choosing to enjoy the quality of country life - with property prices lower than in the capital - while working in London, now easily accessible via the new international stations. This pattern is also evident on the French side, where the advent of high-speed and its traffic have transformed Lille into a labour pool. Northwards past Lille, the TGV serves as a regional train.

Development and future prospects for the British network

Great Britain is currently building a second line (HS2) to link London and Birmingham in central England, in just 49 minutes as compared to the current one hour and 21 minutes, thanks to a commercial operating speed of 360 km/hr. Entry into service is scheduled for 2026. The next step will be to extend this line along two sections originating in Birmingham: one heading towards the north-west and Manchester, and the other eastwards to Leeds. These future lines will surely exert considerable transformation upon the economic hubs of Great Britain, bringing them closer to the capital. They are eagerly anticipated to reduce traffic for the country’s heavily congested motorways. For its part, Belgium has already completed construction of its high-speed network. Significant rail developments were carried out to connect the network to Zaventem Airport, north-east of Brussels.

a selection of HIGH-SPEED LINES by creation date

1964

TOKYO > OSAKA

1992

TURIN > NAPLES

1992

MADRID > SEVILLE

2002

COLOGNE > FRANKFURT

2008

BARCELONA > MADRID

2010

SEOUL > BUSAN

2011

BEIJING > SHANGHAI

2014

ANKARA > ISTANBUL

2014

LANZHOU > URUMQI

2016

SHANGHAI > KUNMING

2016

TOKYO > HAKODATE

2016

ZURICH > MILAN

2018

BEIJING > HONG KONG

2018

TANGIER > CASABLANCA